As we have discussed here before, we may be coming to the point where there are no new ideas in public finance tax law. Yet another example: The recent proposed political subdivision regulations hearken back to a similar regulation project on a related topic many years ago, which suffered from many of the same drawbacks found in the proposed political subdivision regulations.

In 1976, Treasury issued proposed regulations (41 Fed. Reg. 4829) that would have codified a specific definition of a “constituted authority” of a State or political subdivision that can issue tax-exempt bonds on its behalf. These concepts are similar to the concepts that we find in the proposed political subdivision regulations, but the result is somewhat different. An entity can be a constituted authority of either a State or a political subdivision. (See here for prior coverage of this topic.) Prior to the proposed constituted authority issuer regulations, issuers looked to a series of revenue rulings (the first of which was Rev. Rul. 57-187) to determine whether an entity was a constituted authority of a State or a political subdivision.

Like the proposed political subdivision regulations, the constituted authority proposed regulations articulated tests that sound eminently reasonable when you hear them for the first time. And like the proposed political subdivision regulations, the devil (or devils) were in the details.

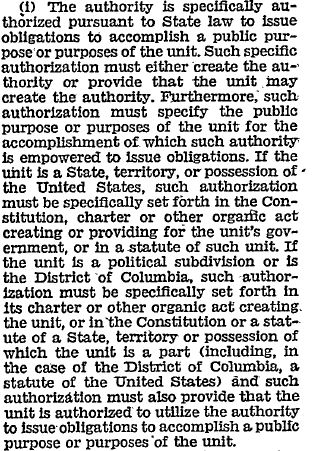

First, like the proposed political subdivision regulations, the proposed constituted authority regulations would have required the constituted authority to serve a public purpose of the governmental unit on whose behalf it was issuing bonds. But the test was quite a bit more specific than that.

As the Preamble to the proposed constituted authority regulations noted: A constituted authority “must be specifically authorized pursuant to State law to issue obligations on behalf of the unit to accomplish a public purpose of the unit.” The authorization would need to specify the public purpose of the governmental unit that would be accomplished by the constituted authority, and the authority would have to be created “solely to accomplish a public purpose of the governmental unit.”

Second, like the proposed political subdivision regulations, the proposed constituted authority regulations would have required the constituted authority to be controlled by a State or local governmental unit. Again, the test was quite a bit more specific than that.

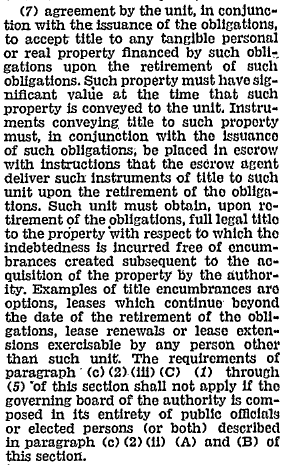

The seventh and final requirement of the organizational control test, which is but one component of the overall control requirements.

The proposed regulations would have required a governmental unit to control the authority’s board. In addition the proposed regulations had specific requirements for the composition of the board, and would have barred a private person from appointing even a small minority of the board. The proposed regulations would have imposed a requirement that certain board members not have a term of more than 6 years. In addition, the governmental unit would need to exercise either “organizational control” or “supervisory control” over the authority. The tests for each of these were exhaustive and exhausting.

Finally, to round out the tests, the proposed constituted authority regulations would have required that no part of the earnings of the constituted authority could inure to the benefit of any person other than the governmental unit and upon dissolution of the authority all property of the authority must vest in the governmental unit.

Each of the elements above are present in very general terms in the revenue rulings that preceded the proposed constituted authority regulations. In its attempt to codify the principles, though, Treasury went far beyond anything that might be considered workable.

After sustained criticism, Treasury withdrew the proposed constituted authority regulations on January 1, 1984. LR-8-73, 1984-1 C.B. 592 (Jan. 1, 1984). In the notice of withdrawal, Treasury stated that “A large number of comments were received, and a public hearing was held on April 26, 1976. After consideration of the comments it has been determined that this notice be withdrawn.” Instead, the tax-exempt bond community could (and still does) continue to rely on prior revenue rulings (such as Rev. Rul. 57-187) to determine whether an entity is a constituted authority of a State or of a political subdivision. Treasury has never again attempted to promulgate regulations on this topic.

It seems that a number of conditions that caused the on behalf of issuer regulations to fail are also present with the proposed political subdivision regulations. Treasury and the IRS have said that the proposed political subdivision regulations are based on commonsense principles and are an attempt to be surgical in responding to a particular perceived abuse – the issuance of tax-exempt bonds by special districts that in Treasury’s view are politically unaccountable. But, as in the proposed constituted authority regulations from 1976, their attempt to codify these principles has gone far beyond even their modest stated goal. As with the 1976 proposed constituted authority regulations, the proposed political subdivision regulations take up the quixotic task of trying to tease apart what activities serve a “public” purpose and which do not. The response to this point so far has been a rather unsatisfying “but it’s a federal subsidy!” That may be, but it seems that a fundamental change to a longstanding definition is better resolved by the fount of the subsidy – Congress – rather than an administrative agency. Given the many similarities between the proposed political subdivision regulations and the proposed constituted authority regulations from 1976, many in the tax-exempt bond community are hoping that the proposed political subdivision regulations suffer a similar fate.